The ashbearer smears my forehead

1.

I want to call him “the ashbearer”, the man who is smearing ash on my forehead.

Dust you are, and to dust you shall return. Turn away from sin and be faithful to Christ.

Ashbearer. Liturgy Co-ordinator. Worship Leader. Ceremonial Leader. All of these names sort of work.

I don’t want to call him “the priest” – because I believe in ‘the priesthood of all believers’ now. That the new covenant is written on our hearts, and that Christ teaches us directly (Jeremiah 31:31-34).

Turn away from sin and be faithful to Christ.

Certainly, there should be no question of needing someone to perform a ritual sacrifice - of “intermediaries”, in general, between the people and God.

I struggle with the practice of vestments, and with “worship leaders” sitting on a higher stage. I don’t believe that only “clergy” can consecrate water, bread and wine.

I’m uncertain what I believe about communion, any more - not that the “essence” of the bread is transformed to become Christ’s actual body. But not that it is a simple “remembrance” ceremony, either. True symbols don’t fit either extreme.

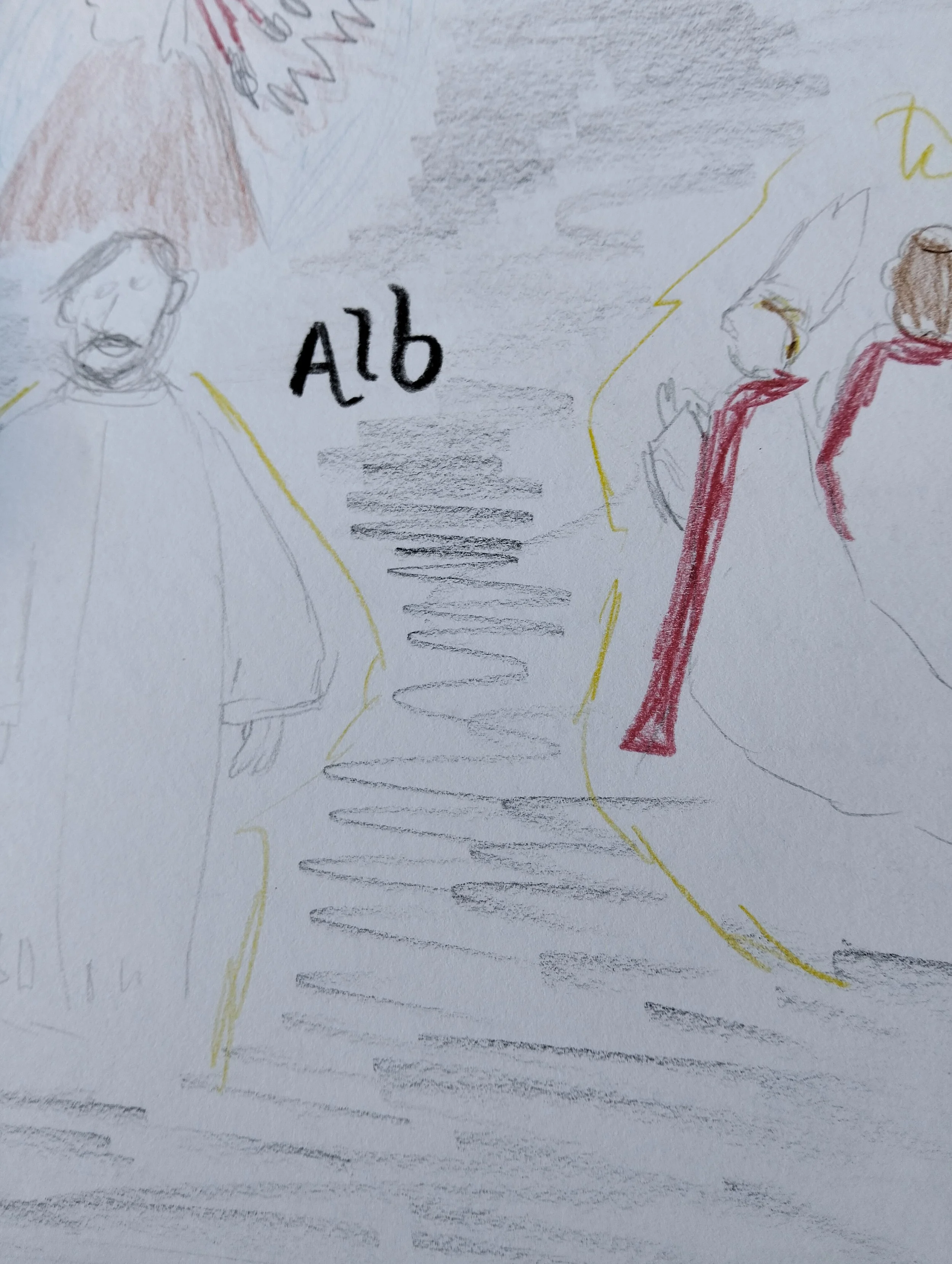

I struggle with the symbolism and inequality of vestments, but I don’t want this man not to be wearing his simple white alb and stole (if you pardon the double negative). They suit this beautiful, circular, Anglican chapel. He wears them without pomp, with little ego.

2.

I am home in Quaker silence and the circle of Friends. It feels like an integrity of the Gospel:

waiting on the spirit, worshipping in spirit and truth, waiting to be taught new things.

It is a tremendous relief to clear away the other items, distractions, clutter.

And yet, Lent is upon me.

I can smell its smoke in the air.

3.

I am home in the heart of silence - because everyone and everything is! It is the heart and womb of the world. It is our heavenly destination when we die.

Of course, I experience ongoing resistance to this “home”.

Turn away from sin and be faithful to Christ.

Silence has no beginning, middle, or end. It illuminates the Things of the World, which are finite.

Silence plus Things equals Presence.

4.

I wait in silence with A New Zealand Prayerbook beside me. Sometimes I just stay waiting.

Reading and listening to scripture out loud – and Anglican common prayer is often carefully arranged scripture – feels sacramental. I feel deeply refreshed and whole again, like the sun that glows before dusk.

But not if I read scripture silently in my head!

I have one rule for reading poetry: read it out loud. You need to intone it. It needs to become verbal and sonic shape.

In the beginning was the Word…and the Word became flesh…

5.

Silence illuminates the world of Things, the world of the Real. This is the Mystery of Christ.

Bread, water, fire, air. A possum’s cry in the night.

Gulls wheeling above the Meetinghouse.

6.

In the Quaker way, we turn to the Light Within.

Stay inside, says Fox,

and when they say ‘Look here’, or ‘Look there is Christ’, don’t go out there, for Christ is inside you. And those who try to seduce your minds away from the teaching inside you are opposed to Christ. For the portion is inside, the light of God is inside, and the pearl is inside, though hidden. And the word of God is inside you, and you are temples of God, and God has said he will make his home in you and walk with you. So why go to the temples of idols outside you? (1)

Positively, this guides us to our own direct experience and discernment: to encounter the Spirit directly for ourselves, and to allow the Spirit to guide us in wisdom and in truth. If we take this away, Christianity loses its radical heart and direct, personal contact with the divine. We come to rely on experts, on hearsay. Religion becomes the opium of the people. We swallow someone else’s experience of the divine - ok for St Paul, in his circumstances, maybe. Ok for Rowan Williams, or Reverend So and So. But what can you say for yourself? That is Fox’s enduring, thunderous challenge.

7.

Sometimes, when we go into the heart of silence, we enter the world of soul. Images spontaneously appear, and then sequences of images. Such visions and visionary quests can be entered into - with wit, wisdom, and discernment. And with the light of the Spirit to guide us in the dark.

This is the same world as the world that we enter when we dream. As Morton Kelsey has often argued (2), receiving and paying attention to such spontaneous images (and words) has a strong claim to being one of the oldest and most perennial forms of “Christian meditation”:

I will pour out my spirit on all flesh; your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions. (Job 2:28).

Following and working with such visions can be ultimately edifying, illuminating, or just concretely helpful in finding our way in life. But the journey is seriously fraught. How do we discern the Spirit’s voice from our own neurosis, trauma, or worse? How do we keep our footing when the inner world is a blizzard? We need a community of support, of people who have walked this journey too, to support us, if not guide us within. (3) Such people are extremely rare these days.

On Shrove Tuesday this year, I sat down and silently ‘waited on the Spirit’. I never quite know what will happen in meditation. Sometimes, the sensations in my body become foreground. I may simply watch and breathe as pain and tension dissolve, or flusteredness and anxiety are replaced by feeling more solid and centred. Othertimes, I might simply rest in the silence, or perhaps hear a possum cry in the night, and smile.

But this Shrove Tuesday, as I sat and became very relaxed and open, some images began to appear.

The first image was of an American First Nations man wearing a colourful, feathery headdress. Why on earth am I seeing this? I thought.

Many meditation traditions treat such spontaneous, deep images as dross, as the rubbish of the psyche that gets released when we relax and begin to unwind, so to speak. Such images are treated as distractions from the process - of union with God, of enlightenment etc. When I started practising Experiment with Light, a Quaker-based meditation practice, I tried receiving and paying attention to such images, rather than just ignoring them or pushing them away.

After the image of the First Nations man and his headdress, I then heard the word “alb”, and saw a young, bearded Christian priest wearing a simple white alb. Then Anglican bishops kneeling in their white albs and red stoles. Why on earth am I seeing this?

Finally, some images about clothes and me, ceremonial sort of clothes (I refuse to use the word vestments!): A crocheted, black shawl with colourful, circular ‘medallions’. I put it on. As soon as it touches my shoulders, the garment becomes pure, gleaming white. The words “hope” and “blood” appear.

I sit with the images in silence and stillness, “waiting in the Light” for some clarity of their meaning for my life. I don’t get anything much, though the events of Ash Wednesday connect up with the vision, in a way (events in both Anglican and Quaker worlds). Is it a vision of my ‘inner priestly vestment’? I say I believe in the priesthood of all believers, but I squirm at this possibility (being a priest) as I write these words. Or is it something yet to be revealed on the Lenten and Easter road - hope, blood, becoming purified?

For now, I want to observe that going within, sometimes, takes us deeply within - to the world of soul - where we are much less aware (or perhaps even quite unaware) of the phenomenal world around us.

As the light illuminates and activates your conscience it will…let you see things that can’t be seen [by the physical eye], but can be seen by the invisible [source of seeing] within you…And this invisible [source of seeing] is the light inside you, which you have been given a portion of by the one who is invisible. This will let you see your heart. (4)

I would also like to simply note that the inner world is deeply symbolic in character. This doesn’t mean it is unreal, but to treat it as either literally true or complete frothy nonsense won’t get us very far. We need to cultivate our capacity to receive and handle symbolism, which modern Christianity, of all theological stripes, isn’t very good at. The Quaker tradition, despite Fox’s own innate capacity to work with inner symbols, has generally disregarded - and often fulminated against - symbolic liturgy and wisdom.

In other words, and to link back to the theme of this post (I hope), even our inner soul is full of the Things of the World - of sensible, tangible shapes and textures.

8.

And then sometimes we go into the heart of silence and no images come at all. We become very centred and still. A possum calls out in the night.

Here, the boundary between “inner” and “outer” dissolves, or simply doesn’t exist.

Or: I am simultaneously “within” my body (which many times, of course, being scattered or outwardly focussed, I am not), and I am receiving “the body of the world” as well, hearing the cicadas around me as I type.

This is perhaps where the language and liturgy of the Light Within is less helpful. As one of my beloved Quaker elders once exclaimed in Meeting for Worship, The Light is Within and Without!

6.

When the ashbearer smears my forehead, and says:

Dust you are, and to dust you shall return…

I am pierced. I quake. Tears form in my eyes.

It is so humbling and beautiful to be reminded of my essence, and of the sadness that this form will die.

7.

Autumn comes as a whisper. A clump of golden, poplar leaves. Oaks bronzing at their tip-ends…

8.

dust: I am not thinking of bits of dried skin, clay, dirt, and hair.

I think of the cosmic dust, without thinking.

It’s a tremendous homecoming. Tears fall on my lap.

References

(1) George Fox (1652) quoted in Rex Ambler (editor and translator), Truth of the Heart: An anthology of George Fox (2001), p.13.

(2) See, for example, Morton Kelsey, The Other Side of Silence (1976).

(3) Kelsey’s The Other Side of Silence is the best modern work that I know of, and one of the only works that I know of, that speaks about this difficult but also rewarding inner journey, world, and work from a Christian depth perspective. Jungian therapists and depth-oriented psychotherapists are also uniquely trained and experienced in navigating such terrain. One of the early surprises of my Quaker journey was discovering that George Fox knew this territory well, too, and indeed wrote helpfully to many others who were struggling to navigate their spiritual world or inner-seeing capacity. The best collection of Fox’s writings regarding this, that I have found, is Ambler’s anthology and notes (above). The Quaker-based meditation practice of Experiment with Light, created by Ambler out of his contact with the writings of early Friends, is a safe, modern way to encounter and navigate the world of soul. See here for more.

(4) Fox (1647), in Ambler above, pp, 29, 31.