Inner breathing

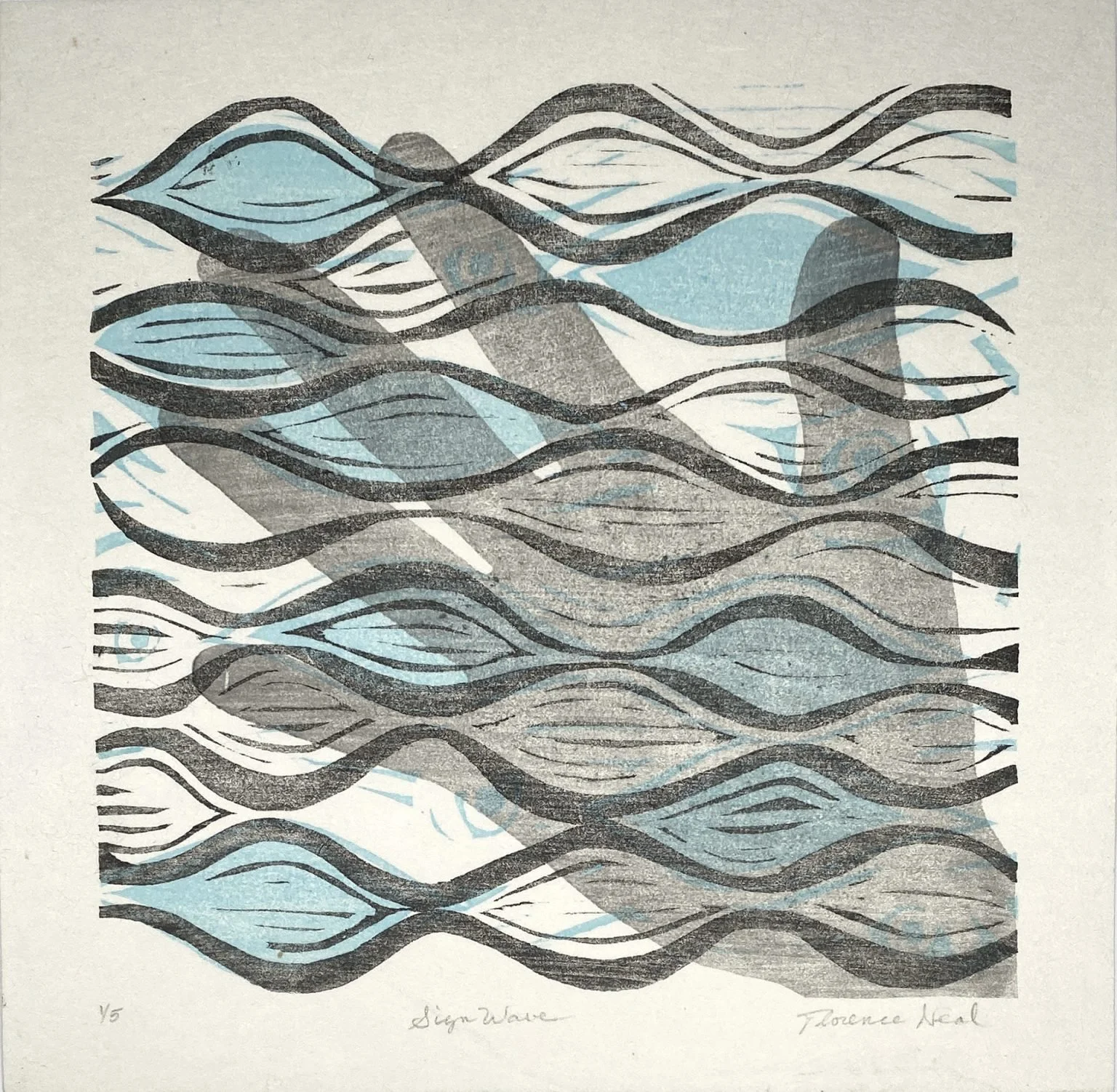

Sign Wave, Florence Neal

When feeling is established, when we have a steady sense of stillness and fullness, our breathing naturally opens and deepens, radiating energy within.

With steady attention within, with full feeling, our breathing can be subtly directed to interact with the stillness and fullness inside, with what Isaac Penington called “the seed” (see below).

We can breathe into the heavy, pleasant, fullness in our hands or feet or belly etc. Or, more simply, without forcing or directing it in any heavy way, we can just let the breath open and deepen, and watch as it spontaneously circulates energy through our body. We just watch, keep breathing, and let the breath “hook” the energy within (“the seed”) and circulate it as it will. The seed begins to grow.

There are ancient and contemporary traditions and sciences devoted to cultivating and circulating the breath and the inner-life force for healing and vitality. Some authors and traditions advise consciously directing the breath into various parts and ‘centres’ of the body. Such practices are undertaken in order to heal specific symptoms and ailments, or to awaken, energize, and regulate various physical, emotional and spiritual ‘centres’ within. This can be useful and even life-changing, but should only be attempted by those with special training, supervision, and a solidly grounded meditative practice. This is intense work, although it may not always feel that way, and sometimes we can become quite undone in the process, going into places we aren’t physically or otherwise prepared for.

In my own experience, it’s very easy for consciously directing the breath to become too effortful and controlling. The mind or ego takes over, and our opening to spirit closes over.

My preference is to bring feelingful attention to the breath, to allow it to open and deepen, mostly of its own accord, and to gently participate it its spontaneous movement - to give it a gentle nudge at the bottom and top of the inhalation-exhalation cycle, for example. To offer a small amount of conscious participation and willing effort in terms of going-with its natural opening, deepening, and radiating. The breath seems to respond very favourably to such an approach.

Inner breathing, for me, is a partnership - one in which we bring some minimal focused effort while for the most part surrendering to the ‘wisdom of the body’ - or the wisdom of the holy life-breath itself. It is a ‘yoga’ (union) of feeling-consciousness and matter, the subtle and the manifest, will and grace.

“South Wind, Clear Dawn”, Katsushika Hokusai

Breathing in this way is a very simple, effective form of becoming more solid and grounded in our spiritual practice, like a mountain at dawn. It can help with a sense of inner safety and containment as we journey within. If we ever bump into experiences that feel overwhelming, unsafe, or even terrifying, we can simply return to our breath, to inner breathing, to the mountain.

Inner breathing also allows us to disperse excess energy, emotion, and sensation that can accumulate - comfortably or uncomfortably - as wait on and experience the spirit. Other ways of safely dispersing such abundant inner ‘charge’ include spontaneous singing, speaking in tongues, moving, dancing, shaking, and, indeed, “quaking”. Of course, these aren’t just ways of dispersing ‘excess charge’, but can also be genuine forms of worship and spiritual life.

Despite rich reflections on breath and wisdom in some Biblical literature (see below), and not including some esoteric instruction on breathing in Orthodox hesychasm, Christianity hasn’t developed formal, breath-based spiritual practices. Or has it? Could it be that the breath - and its centrality in Christian spiritual experience - has been hiding in plain sight, as it were?

Scott Martin (see below) has argued that references to “the power” or “the power of the Lord” (one of the most central concepts of early Quakers, though much ignored ), as well as the eponymous phenomenon of quaking itself, are evidence of a much more embodied, dynamic spiritual practice than subsequent Quakers (evangelical and liberal) have acknowledged and understood.

One seventeenth century Quaker author who explicitly mentions breathing, in relationship to contemplative practice, was Isaac Penington (see below).

What follows is more gathered wisdom on the breath and inner breathing.

“The Bright Cloud”, Samuel Palmer

Isaac Penington (1616–1679), early Quaker writer and mystic:

“Give over thine own willing, give over thine own running, give over thine own desiring to know or be anything, and sink down into the seed which God sows in thy heart and let that be in thee, and grow in thee, and breathe in thee, and act in thee, and thou shalt find by sweet experience that the Lord knows that and loves that and owns that, and will lead it to the inheritance of life, which is his portion.” (1)

“As for praying, they will not need to be taught that outwardly; but if true sense be kindled in them, though ever so young, from that sense will arise breathings to Him…” (2)

“O that you might feel the breath of life, that life which first quickened in you, and which still quickeneth!” (3)

“Keep cool and low before the Lord, that the seed, the living seed, may spring us more and more in thee and thy heart be united more and more to the Lord therein.”

Ruth Tod adds:

“Keep cool and low is an invitation to bring our attention and breath right down to the abdomen, to become really calm and in touch with the core. Welcome the nourishment of the earth and gather it up into your breath and your heart, so that the seeds within grow and spread within you. Feel it, he says over and again.” (4)

From Scott Martin, ‘The Power,’ Quaking, and the Rediscovery of Primitive Quakerism (2001):

“‘The Power of the Lord,’ or just simply, ‘The Power,’ was a very important concept to the early Quakers, but it is virtually unknown among Friends today. In The Power of the Lord Is Over All: The Pastoral Letters of George Fox, T. Canby Jones notes that Quakers frequently say that Fox’s central teaching was there is ‘that of God in every one.’ Surprisingly, this phrase appears only 108 times in his writings. Variations of the "Power of the Lord’, appear, 388 times, and it is the single most often used phrase in his Journal.

‘The Power of the Lord’ had multiple meanings for Fox and other early Friends, but the most common use of the phrase was to refer to a sensible, divine power or energy. Friends would experience this power surrounding them or flowing through their bodies under a variety of conditions, but most often at the point of convincement, when facing a trial, or during meeting for worship. An experience of the power was often associated with some kind of involuntary physical or mental phenomenon. When seized by the power, some Friends quaked, vocalized, or fell unconscious to the floor, while other Friends saw brilliant light, had visions, experienced healing, or felt a force emanating from them that was capable of subduing an angry and hostile mob.

...While Asian religions conceptualize energy as an impersonal life force coming from within, Christianity tends to use the image of the indwelling of a personal Holy Spirit from above. Both, I think, are speaking about much the same experience.

I believe the energetic experiences of early Friends greatly influenced how they conceptualized their faith. Before Quaker notions such as ‘the power of the Lord,’ ‘inner light,’ or ‘the seed’ were abstract theological concepts, they were, I believe, actual bodily experiences. As John Mann and Lar Short point out in The Body of Light, ‘the physical body is the mediator of all our experiences,’ and this is especially true of our profound religious experiences. The body is truly the temple of the Holy Spirit.

...The writings of Isaac Penington contain many clues to his experiences with energy. Penington’s advice to sink down daily to the seed planted in the heart (a 17th-century term for ‘center’) is identical to instructions that might be given by a qigong teacher today. The Chinese concept of the dan tien is indistinguishable from Penington’s idea of the seed when seen not as an abstract theological statement, but as an actual location in the body. In fact, I thought of Penington immediately when I read the advice of Deng Ming-Dao, a modern-day Taoist: sit still and ‘fertilize the seed within; let it sprout into a flower of pure light’ (365 Tao Daily Meditations). Furthermore, Teresina Havens has pointed out in her pamphlet, Mind What Stirs in Your Heart, that Penington’s references to ‘true breathings’ and the ‘breathing life of the seed’ suggest that he understood the connection between breathing and prayer, and, I might add, the cultivation of energy in his own body. I think Havens is absolutely correct when she implies that Penington’s frequent use of phrases such as the "rising of the power" and “purely springing life” suggests that these were actual, bodily experiences. He says as much when he writes, ‘In your meetings . . . be every one of you very careful and diligent in watching to his power, that ye may have the sensible living feeling of it.’"

....Why is it that the early Quakers had such an intense experience of the power while we do not today? My guess is that the widespread practice of daily retirement in that time may have been a factor. Both Fox and Penington, for example, were known for their ability to sit for many hours at a time. Tranquil sitting is a powerful method of energy cultivation, and although from the outside it may look like the body is inactive, much is happening inside on an energetic level. In abandoning the practice of daily sitting, which might legitimately be called the ‘Quaker yoga,’ modern Friends may be cutting ourselves off from a deeper, more profound experience of worship. It is only logical that Friends who sit only on First Day simply cannot have as deep an energetic experience as those who have done this every day for many years.

....I think the time is right for a rediscovery of the power and daily sitting. Many Friends, like me, are experiencing what Harvey Cox calls an ‘ecstasy deficit.’ We read the accounts of the early days of Quakerism with a certain amount of envy, sensing that there is a greater depth to our faith than we are experiencing today. Worship often feels flat, and we wonder if we are doing something wrong. We feel frustrated that our practice does not seem to transform us. Those traditional Quaker qualities of peacefulness, acceptance, and love seem to elude us. We are tired of reading books about other people’s experiences. We want to get out of our heads and into our bodies. We seek a deeper healing.

Isaac Penington’s advice to the seekers of the 17th century applies equally to the seekers among us today: Oh, sit, sit daily and sink down to the seed and ‘wait for the risings of the power . . . that thou mayst feel inward healing.’

“Shore Break”, Rod Nelson

Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, Indian yogi and teacher:

We have ignored our breath. We attend to our feelings…we attend to our thoughts or concepts, to our memory or to our mind. We attend to the body – trying to lose weight, or gain weight. But there is something, which is connecting all these, that we have completely ignored – and that is our breath. (5)

A disturbed breath leads to a disturbed mind. A steady breath leads to a steady mind. The two go together. Hence cultivate a steady and quiet breath. Thereby the mind is controlled. (Hatha Yoga Pradipika).

Can you focus your life-breath until you become supple as a newborn babe? (Tao Te Ching, poem X; J.H. MacDonald translation).

Kabir, fifteenth century Indian poet:

Are you looking for me? I am in the next seat. My shoulder is against yours.

You will not find me in stupas, not in Indian shrine rooms, nor in synagogues, nor in cathedrals:

not in masses, nor kirtans, not in legs winding around your own neck, nor in eating nothing but vegetables.

When you really look for me, you will see me in an instant - you will find me in the tiniest house of time.

Kabir says: Student, tell me, what is God?

He is the breath inside the breath. (6)

“Cloud Study”, John Constable

God breathed life into the body’s nostrils, and the body became a living soul. (Genesis, 2: 7).

I learned both what is secret and what is manifest, for wisdom, the fashioner of all things, taught me. (Wisdom 7:21-22).

The Nature of Wisdom

There is in her a spirit that is intelligent, holy, unique, manifold, subtle, mobile, clear, unpolluted, distinct, invulnerable, loving the good, keen, irresistible, beneficent, humane, steadfast, sure, free from anxiety, all-powerful, overseeing all, and penetrating through all spirits that are intelligent, pure, and altogether subtle.

For wisdom is more mobile than any motion; because of her pureness she pervades and penetrates all things. For she is a breath of the power of God, and a pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty; therefore nothing defiled gains entrance into her.

For she is a reflection of eternal light, a spotless mirror of the working of God, and an image of his goodness. Although she is but one, she can do all things, and while remaining in herself, she renews all things; in every generation she passes into holy souls and makes them friends of God, and prophets;

for God loves nothing so much as the person who lives with wisdom.

She is more beautiful than the sun, and excels every constellation of the stars. Compared with the light she is found to be superior, for it is succeeded by the night, but against wisdom evil does not prevail. (Wisdom 7: 22-30).

Jesus, speaking to Nicodemus:

I’m telling you: unless someone is born out of water and wind, breath, spirit, they can’t enter the kingdom of God. What’s born out of flesh and blood is flesh and blood, but what’s born out of the life-breath is the life-breath. (John 2: 5-6; Sarah Ruden translation).

References:

(1) Isaac Penington quoted in Bernard Canter (ed.), The Quaker Fireside Book (1952), p.21.

(2) Penington quoted in Ruth Tod, Exploring Isaac Penington (2023), pp.25-26.

(3) Penington, as above, p.26.

(4) Penington and Tod quoted in Tod, as above, p.28.

(5) Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, Punarnava: New Again (2003), p.17.

(6) Kabir, The Kabir Book: Versions by Robert Bly (1977) p.33.